Here’s the thirty ninth installment of LiteratEye, a series found only on The Art of the Prank Blog, by W.J. Elvin III, editor and publisher of FIONA: Mysteries & Curiosities of Literary Fraud & Folly and the LitFraud blog.

LiteratEye #39: What Do You Want To Be When You Grow Up? Somebody Else.

By W.J. Elvin III

November 13, 2009

“My walk will be different, my talk and my name,

Nothing about me is going to be the same”¦”

-From the song lyric, There’ll Be Some Changes Made

There are different kinds of imposters in the field of literary deception. There’s the trickster, such as the false-memoirist in it for the bucks. And then there’s the true believer, the re-invented person who is really into a role.

There are different kinds of imposters in the field of literary deception. There’s the trickster, such as the false-memoirist in it for the bucks. And then there’s the true believer, the re-invented person who is really into a role.

Nasdijj is a trickster. He made claims but actually had no direct experience of the Navajo life he wrote about.

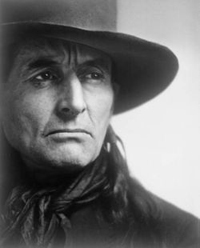

Grey Owl, on the other hand, surely had a trickster streak but he was far more the true believer. He was an English boy, Archie Belaney, who wanted to be an Indian. And eventually, in outward appearance and lifestyle, he became one.

If the imposter Nasdijj has any Indian defenders, I haven’t run across them. But certainly Grey Owl does. One of them is Armand Garnet Ruffo, author of Grey Owl: The Mystery of Archie Belaney. The book is a prose poem that includes tales from Ruffo’s Ojibway relations.

Having read half a dozen accounts of Belany/Grey Owl’s life, I find the “facts” vary from one biographer to the next. Then there’s his own autobiography and other writings, which have to be taken with a pillar of salt.

It’s certainly true that he headed into the deep woods after reaching Canada in 1906, and there Grey Owl was born.

It seems a fact that he was adopted, via traditional rituals, into the Ojibway tribe.

He didn’t exactly become a noble savage. He was irresponsible and had a violent temper. He drank a lot and fought, not only with local whites and tourists but with anything he saw as destructive and invasive. He liked to throw knives at trains, that sort of thing.

When faced with fatherhood in his own life, he abandoned at least two women and children. “A devil in deerskins,” said one of his wives. He hardly knew his own father, who disappeared into Canada leaving his wife and son in England.

Even when he got his act together, Grey Owl was still full of deviltry. “To tell him that somebody he was going to meet was important and should be treated with respect was enough to waken the gleam of mischief in his eye”¦” said Lovat Dickson, recalling how his friend would feign falling asleep in the presence of those he was advised to impress.

Dickson, the publisher whose interest in Grey Owl propelled an obscure backwoods guide into celebrity status, wrote a biography of his friend. He also published a collection of personal memories, press clips and selected writings, The Green Leaf, a fairly scarce item. It was one of the books I rounded up as my interest in Grey Owl grew, a little treasure to add to the LiteratEye collection.

Archie tried but couldn’t escape all of civilization’s discontents. He served in the First World War as a sharpshooter, returned wounded to England and married a woman he had known in his school days.

Then he headed back to Canada, intending to bring his new bride over later. But when the lady learned of his former marriage, which had never been officially dissolved, that was the end of that. And Archie went back to being an Indian.

Archie hooked up with Anahareo, an Iroquois woman who hated the way whites slaughtered the wildlife for profit, especially the beaver and other fur-bearers. Soon they were raising orphaned beaver kits and trying to establish a refuge.

Already a foe of aspects of white civilization that were destroying the Indian way of life, Grey Owl became a defender of wildlife and of the woods that were being decimated by loggers. He found a mission in life, preaching conservation and Indian rights through stories and public appearances.

By all accounts, he really became a St. Francis of Saskatchewan.

By the mid-1930s, thanks to his skill as a writer and public speaker, Grey Owl was “the most famous North American Indian in the world.”

The best of his writing might be found in Grey Owl: Three Complete and Unabridged Canadian Classics. A search by name on one of the major book conglomerates will turn up not only his own books but many about him. Some of the films he made in his campaign to save the beaver population may be found on the Internet.

It’s hard — for me anyway — to fault a guy who found a very successful way to express his love of nature and to change the way many others saw the wilds.

And there was one other thing that made me think we might have been pals, had circumstances allowed. He wrote in the jargon or lingo he had come to know in the camps and lodges, and his proper English proofreaders didn’t approve. They corrected his words and sentences. His response indicates to me that he was hardly in it for the money:

“If, every time I write a book, some outsider, having no knowledge of this country or its people, interposes his own idea, and there is to be continual bickering and fussing and exasperating worry over so great a distance, I’ll just drop the whole business; everything. “¦ I stand ready to dump everything overboard, the whole business, and forget my flutter in the literary world. It isn’t worth it.”

There’s much more, biographically, to the story. Richard Attenborough’s film seems fairly true to life, perhaps streamlining Grey Owl’s zig-zag romantic involvements for the sake of a seamless story.

That story might have dragged out into an unhappy life lived under the dark cloud of exposure. The newshounds were on the trail of the truth, that Grey Owl was Archie Belaney, born of British parents in Hastings, England, in 1888.

But he didn’t stick around for the media attack. Sick and tired, home in his beloved northwoods after two very successful but exhausting lecture tours, he died at age fifty.

Maybe you’ve got an answer to one final question: Who died?

One of his last remarks was typically theatrical but at the same time, at least to those who share his turn of mind, a deep truth:

“I came out of the shadows to do my work, and into the shadows I shall return.”

photo: Yousef Karsh

(Copyright 2009 WJE, exclusive to The Art of the Prank, for reprint rights contact Literateye@gmail.com)

Check out previous LiteratEye episodes on The Art of the Prank.