This is a disturbing story about an unbelievable travesty of justice. A 15 year old boy was convicted of murder twenty years ago and received a life sentence with no possibility of parole. His conviction was based on faulty circumstantial evidence; analysis of his art work; and the fact that he did not report the body, which he saw lying in a field as he rode his bicycle to school, because he thought it was a prank. JS

Sketchy evidence raises doubts

Revisiting a conviction

by Miles Moffeit

Denver Post

July 14, 2007

Somewhere between the spot Peggy Hettrick was abducted and the Fort Collins field where her partially clad body was dumped, her killer would have shed pieces of himself, mothlike.

As he pulled her through the grass that dark morning on Feb. 11, 1987, his skin cells could have sloughed off onto her black coat. A strand of his hair could have hooked onto her shoes. A sneeze could have dampened her blouse.

This is the law of forensic science: When two people come into contact, they leave cells on each other.

But in the Hettrick murder case, authorities strayed from this law by losing some of these biological relics and destroying evidence linked to a prominent doctor they never investigated for the crime. In doing so, they may have covered the killer’s genetic tracks.

This happened in Fort Collins, where a detective clung to his belief that a 15-year-old boy committed the crime, despite no physical evidence. In a county where prosecutors opposed saving DNA, let alone testing it. In a state where the law doesn’t create a duty to preserve forensic evidence.

The result, as believed by three former Fort Collins police detectives and a former Colorado Bureau of Investigation director: An innocent man goes to prison for life, and the real killer moves on.

“It eats me up,” says Linda Wheeler, one of the officers. “I’ve put people in prison for murder. I make people accountable for crimes they’ve committed. But I’ve felt we have two victims here. One is in a jail cell in Buena Vista.”

The story behind Hettrick’s murder and Tim Masters’ conviction is one of inferences blurring with facts, character issues blurring with guilt and theater blurring with truth.

Twenty years after Hettrick’s killing, Masters’ legal team has launched one of the most ambitious and expensive bids ever in Colorado to prove a man’s innocence – nearly $500,000 provided by the state legal defense system. The effort has led them to a small laboratory in the Netherlands, where a smudge of skin cells has been mined from Hettrick’s clothing using the most-advanced DNA techniques available.

The skin was found where the killer’s fingers would have roamed.

Tests show it wasn’t Masters’.

The discovery

A bicyclist phoned in the news just after sunrise from a south Fort Collins neighborhood.

At first, he thought he had seen a mannequin in a field along Landings Drive. She was so white.

She was a small woman, about 115 pounds, with flaming-red hair. Her bra, blouse and black coat had been pushed up above her breasts; her panties and bluejeans had been pulled down to her knees.

Her eyes were open, her arms outstretched among the brown leaves, her purse looped above one elbow. Blood, presumably from a knife wound to her back, trailed 103 feet from her body to a small pool by the street curb. Tiny abrasions marked her right cheek.

Among the oddest features: Her left nipple and areola had been carefully removed and the front of her body was wiped clean. No blood.

Police identified her as Peggy Hettrick, 37, college dropout, barhopper and aspiring writer who worked at The Fashion Bar, a nearby clothing store. She was last noticed abruptly leaving The Prime Minister, a restaurant only blocks from the field, about 1:30 a.m. Earlier, at the restaurant, she had seen her on-and-off boyfriend with another woman.

Her friends privately worried something horrible would happen to her, given her late-night impulses, her jealousies, her appetite for adventure. Sometimes she would head out into the night just to collect details for the book she was writing or to spy on her boyfriend. In a drawer at her home was a half-written, neatly typed novel about diamond smugglers and their obsessive search for jewels. The first chapter ends with murder; the last stops mid-sentence.

That day in the field, investigators wrapped paper bags around Hettrick’s hands and feet to capture skin or hair she might have scratched off her killer and any specimens her footwear might have picked up. They found two hairs – not hers – on her footwear. In her purse, they lifted 13 fingerprints, also not hers.

Larimer County Medical Examiner Dr. Pat Allen later found the most puzzling wounds, unnoticed by officers. They were “neatly” executed cuts inside her genitalia that, like the one on her left breast, must have been made with an extremely sharp knife, an instrument different from the one used to stab her.

In 21 years of performing autopsies, Allen told colleagues, he had never seen wounds like these.

Son may have seen something

The police dragnet fanned across Landings Drive to the east, where new luxury housing sprawled, and to the southwest, where blue-collar folks still lived in trailers.

Officers knocked on dozens of doors to see what anyone saw, heard, suspected.

From a mobile home 100 feet south of Hettrick’s now-covered body, Clyde Masters told Wheeler of the Fort Collins police that his 15-year-old boy had walked through the field to his bus stop, as he did every morning. Tim may have seen something, he told her.

After Wheeler relayed this to fellow officers, Masters, a sophomore at Fort Collins High School, was pulled out of class.

Yes, he had seen a body, he told police. No, he didn’t report it. He first thought it was a mannequin, as the bicyclist did, but he didn’t know for certain. On the bus, the image nagged at him. He wondered whether a prank had been played on him. Read the rest of the story here. Watch a video documentary about this case here.

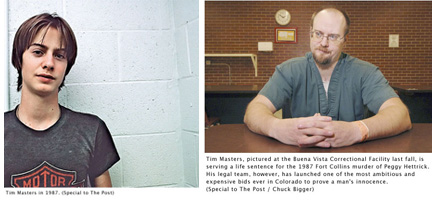

Tim Masters then and now: