Nick Confalone confesses all… in a Los Angeles Times OpEd piece

Revenge of the Hollywood desk slaves

Hiding behind a website, one of Hollywood’s lowliest creatures creates an instant — and all too hot — hit.

By Nick Confalone

April 22, 2007

Nick Confalone, a former assistant to a Hollywood movie producer, now works in television animation.

For four weeks in April of 2006, I was an Internet celebrity. In one industry, in one city, I was a star. The blogs went crazy. Defamer was all over me. National Public Radio wanted an interview “” but I turned them down. My site got more than a million hits in 24 hours.

It all started one morning the previous December, the same week the Hollywood Reporter listed the 100 most powerful women in Hollywood “” the trade’s equivalent of a swimsuit issue.

The first thing I did that morning was run to Starbucks and get my boss’ drink of choice, a double tall latte with caramel sauce, not caramel syrup because “it tastes like trans fats.” I was a Hollywood assistant, one of hundreds of young, ambitious college graduates in L.A. getting coffee that morning. It was always better to get the coffee before we got busy rolling calls. (Rolling calls, for the uninitiated, is when an assistant acts as a telephone operator. The boss calls from out of the office. Then, with the boss still on the line, the assistant calls someone else and links them together.)

That morning, my boss told me to work on urgent tasks, so I skimmed the 100 Most Powerful Women list for hotties or notties. Successfully finding both, I considered my first urgent task a success.

I read the Hollywood Reporter not because I loved it, particularly, but because it was part of my job as an assistant to a successful movie producer. I was the eyes and ears of my boss. I answered phones all day, rolled calls to him when he was out and only saw celebrities as they walked past my cubicle.

Hollywood assistants spend every minute of every hour of every day at a computer, the Internet at our fingertips, a telephone headset connecting us to the outside world. On a daily basis, I might’ve rolled 500 calls “” and it was always another assistant who answered the phone. We did each other favors and kept scores and made enemies and backstabbed, and most of the time we’d never even met. The assistant subculture is a Zen koan: Everyone knows everyone; no one knows anyone. And if assistants do happen to meet in person, their names really don’t even matter. “I’m Alex McArdle.” Pause. “From Tom Hanks’ office.”

Taken as one entity, assistants form the biggest brain in Hollywood, a living network where information spreads via e-mail at 120 words per minute. As individuals, they operate alone in a vacuum, vaguely aware they’re part of a community that doesn’t really exist.

Over the phone that morning, I gossiped about the list of 100 Powerful Women, women I’d never seen before. I didn’t need to see them. The list said that looks don’t matter, only power.

But because we have little or no actual power, the opposite must be true for assistants. If an agent gets a new assistant, the first thing my boss always wants to know is, “Is she hot?” I looked around our office and saw not a single unattractive assistant, and that’s when it hit me: Don’t the assistants deserve a list too?

I pulled out my credit card, registered a domain name, and Hottest Hollywood Assistants.com was born.

*

Lunch is at 1 o’clock, every day, no exceptions. Our bosses disappeared to Ammo, Art’s Deli, Ivy “” wherever we told them to go. Assistants usually can’t leave their desks, so I ate a sandwich and sent instant messages to a co-conspirator. Together, we sketched out the website. Unlike the Hollywood Reporter’s list, we’d judge Hollywood assistants based only on their looks. We decided to include male assistants, like ourselves, because we didn’t want anyone to accuse us of being sexist. (I’m now aware that intentionally “including men so we don’t seem sexist” definitely makes an already sexist idea even more sexist.)

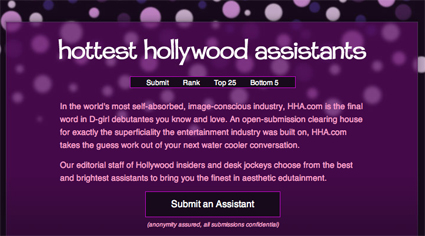

On the site, users would be able to upload photographs of themselves or others “” along with vital information like “boss” and “company.” As soon as they clicked “submit,” these mini-profiles would automatically drop into a randomized queue where other assistants could spend hours browsing pictures of people they’d only heard speak on the phone. The interactive part: Visitors to the site would rate the assistants on a scale of 1 to 10, and the website would automatically generate a Top 25 list. The website theoretically ran itself.

We realized that if something went wrong, there was a good chance we’d Never Work In This Town Again. So my partner-in-crime became D’Wayne Alpental (self-described as “half-black, half-Swiss”) and, by the time my boss got back to the office, I had transferred control of the website into the very capable hands of my own alter-ego, Leo Roquentin. What can I tell you about Leo? He comes from money, he’s trilingual (c’est vrai), and he’s an all-American athlete. Leo Roquentin would be the public face of http://www.hottesthollywoodassistants.com. I stepped back and let him run the show.

*

The site went live on Friday, March 24, 2006. A few days later, we posted a “grand opening” announcement in Craigslist’s classified ads. We hoped an assistant would see it and post it to his “tracking board,” an e-mail list made by assistants to share information about new scripts, new jobs and, apparently, new websites. With the infrastructure already in place, news of our site spread like malaria.

Within hours, I was pounded by e-mails from every assistant I knew. They didn’t know I was behind it; they just wanted to share the hilarity, and gossip about the Top 25. Apparently, the news spread all over town, because by the next morning, we had more than 1 million hits. Visitors kept coming, and we exceeded our monthly bandwidth in four days.

For one week, chaos reigned over a 20-mile radius in Los Angeles. Hollywood gossip blogs declared it “an online beauty pageant for the industry’s desk slaves.” CAA went so far as to block our IP address, but it was too late; we were unstoppable. I scrambled to keep up with the site’s exponential growth.

For one thing, Leo was swamped with e-mail from assistants all over the city. Some I knew (I responded to their e-mails and pretended I didn’t see them on a weekly basis); some were excited (one assistant said her boss was proud of her). But most were unhappy (“Remove me immediately” or “I am not a 3.3!”)

Although many assistants seemed to get the joke, almost every assistant working for a high-profile boss demanded to be removed. I guess it’s bad enough they have to fold 200 origami frogs for their boss’ Passover seder; they don’t need extra humiliation. One of Scott Rudin’s assistants “” a man “” was submitted every few hours, always with different embarrassing pictures and different malicious comments. Rudin’s office promised legal action if I didn’t remove him.

To quell the fury, I signed every apologetic e-mail from Leo with a suave invitation to drinks. Female assistants were usually happy to meet. Girls liked Leo Roquentin more than they liked me. I briefly toyed with the idea of following through with drinks, incognito with a French accent and optional monocle. But I shelved the idea when I couldn’t even grow a convincing mustache. In fact, I looked like I hadn’t slept for days. Leo was an Internet celebrity, and I was a mess.

Managing our sudden rise to Internet celebrity became more time-consuming than the site itself. Thanks to Hollywood gossip blogs like Defamer, our server troubles were public knowledge; our rankings became a matter to debate over drinks at Mosiac. People wanted to see what was next for the Leo and the site. As far as I was concerned, there was no way to top ourselves, no way to keep the joke going.

So a couple of weeks later, I faked a lawsuit against the website. I leaked a bogus cease-and-desist letter to the Internet, a “demand for immediate retraction of false and libelous statements.” It stated that we claimed “to accurately assign numerical values to the beauty of Hollywood assistants. In fact, any reasonable bystander would assign [our client] a value much higher than your website did.”

At this point, even National Public Radio got in on the action. They wanted an interview with the wizards behind the site; the producer told us we “contributed to and changed an ultra-current phase of sociology.” I declined the interview (much to Leo’s dismay) to protect my anonymity and what was left of my day job.

*

Assistants are a captive audience, and the Internet is their television, but it didn’t take long before they changed the channel. The website’s explosive growth fizzled after a month. Traffic leveled off to a few visitors per day, and we slowly disappeared from the public’s consciousness. Other stories spread through the tracking boards. Though the website is still up, our story was soon forgotten.

Leo once called the website a pinnacle of 21st century entertainment, a piece of culture-jamming post-postmodern art. I may not entirely agree with him, but I’d certainly call it a valuable lesson in publicity. I watched firsthand as Leo hijacked the Hollywood subculture and used its obsessive information-sharing network for personal gain. The machinery of fame was waiting; I just had to turn it on.

And you can do it too. We live in a world where anyone with an Internet connection can exploit the culture of celebrity. And isn’t that knowledge more valuable than the vast fortunes I could have made from Google ads? Yes, and no. (Mostly no.)

At least it was better than rolling calls.

© 2007 Los Angeles Times