JadedAid, a new party game derived in style and spirit from Cards Against Humanity, satirizes the international development industry in brutal and hilarious fashion.

Cards Against Humanitarians

by Iyla Lozofsky

Foreign Policy

September 28, 2015

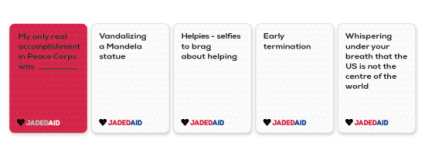

Needless to say, this very serious industry has its very serious critics. But few are as creative (or as hilarious) as three young development professionals who, in the last few weeks, have chosen to express their discontent by self-publishing a satirical card game. JadedAid is modeled on the popular millennial game, Cards Against Humanity, in which players compete to select the funniest (or most vulgar) answers to a set of “fill-in-the-blank” questions. Just a week since its opening, the JadedAid KickStarter campaign has collected nearly twenty thousand dollars “” far ahead of its creators”™ targets “” and the game is well on its way to completion. As an example of the kind of decidedly un-pc satire the game provides, here is one possible combination of cards:

Some of the card ideas were developed by the game”™s inventors, who, all in their thirties, have extensive experience in the technology and communication side of the development industry. But the vast majority of the suggestions (nearly 800 at last count) were submitted by friends, colleagues, and anonymous development workers. One of the game”™s co-founders, Jessica Heinzelman, 36, attributes the game”™s immediate appeal to the need for development workers to “let off some steam” by subjecting their experiences in the field to mockery. Continue reading “The Squicky Side of International Development”