An ode to a political prankster

by Tom Lawrence

Black Hills Pioneer

June 12, 2018

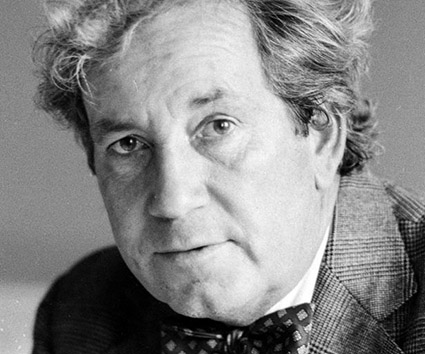

Even his name, Dick Tuck, which rhymes with Puck, was perfect.

Because Dick Tuck was a Puckish presence in national politics for decades, using wit and wile as weapons in political battles. The Democratic trickster died May 28 at 93 … unless this was another of his pranks. I really wouldn’t put it past him.

Tuck’s primary target was another Tricky Dick, aka Richard Nixon. From Nixon’s bid for a Senate seat in 1950 until his presidential re-election campaign in 1972, Tuck was a thorn in Nixon’s flesh, poking and prodding him with stunts, pranks and mischief.

Why? Tuck had a deep dislike for Nixon, and not just because they were polar opposites politically. He felt Nixon was unethical and unprincipled — a good read, it turned out — and Tuck was determined to do whatever he could to hamper his rise.

It rarely worked, however. Nixon won the Senate race in 1950, defeating Democratic incumbent Helen Gahagan Douglas, whom he labeled “the Pink Lady,” unfairly and inaccurately accusing her of being soft on communism.

Tuck launched his political career during that race when a college professor who knew he was interested in politics asked him to aid the Nixon campaign. He forgot to ask which party his student favored.

Amazingly enough, Tuck was allowed to organize a Nixon rally. He booked the largest hall he could find and did not publicize the event. He then introduced Nixon with a long, rambling speech that ended by telling the scant few people in the audience that the candidate would discuss the International Monetary Fund.

After the shambles of an event was over, Nixon went to the young organizer and said, “Dick Tuck, you’ve done your last advance.”

If only he had known what was in store for him.

Over the next 20 years, Tuck pinned a “Nixon’s the One” button on a pregnant black woman and had her walk around before an event in a conservative area.

When Nixon was running an unsuccessful campaign for California governor in 1962, Tuck had signs written in Chinese presented to Nixon. However, they asked about a large loan Nixon’s brother had obtained from billionaire Howard Hughes, which was a campaign issue.

When Nixon learned of the deception, he grabbed a sign from a bystander and tore it up in front of a TV camera. Once more, Tuck had struck.

In the White House recordings that were released during the Watergate scandal, it was revealed that Nixon had both an intense dislike for Tuck — which was no shock — and a grudging admiration for him ability to bedevil him and get media attention for his stunts.

When Nixon aides and supporters tried such techniques, they lacked Tuck’s wit and light touch. Donald Segretti failed in his efforts to mess with Nixon’s opponents, as the president admitted.

“Shows what a master Dick Tuck is,” Nixon said in an Oval Office conversation caught on tape on March 13, 1973. “Segretti’s hasn’t been a bit similar.”

After Nixon resigned in 1974, Tuck remained involved in politics, including working for South Dakota Sen. George McGovern and the national Democratic Party. But without his favorite target, Tuck slipped from the spotlight.

He ran for office just once, losing a state Senate race in California in 1966. Tuck’s response was typically funny and original.

“The people have spoken,” he said in his concession speech. “The bastards.”