Mood Swings at Beijing”™s Water Cube

by Clarissa Sebag-Montefiore

Wall Street Journal

June 25, 2013

Beijing”™s Water Cube is perhaps best known as the place where Michael Phelps won eight gold medals. This week, it became the site for something altogether different: a real-time “painting” of China”™s mood, as revealed by Sina Weibo emoticons.

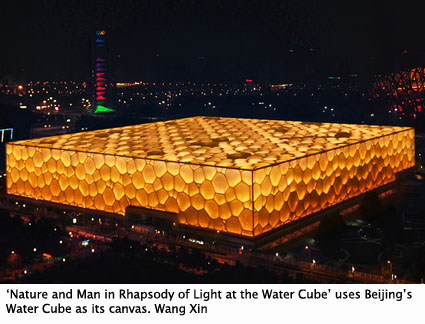

“Nature and Man in Rhapsody of Light at the Water Cube,” a collaboration between the artist Jennifer Wen Ma and lighting designer Zheng Jianwei, opened last Sunday. Using the former Olympics venue”™s distinctive exterior, it broadcasts the sentiments of the Chinese social-media service”™s millions of users through an interactive lighting display that runs from dusk to 10 p.m. daily.

“I have conceived this as a piece that can breathe,” says Ms. Ma, who turns 40 this week, “as an organic being that changes as nature and society around it changes. I want people to feel like they have some authorship because their emotions are being registered.”

A custom software application sifts through millions of smiley faces and other emoticons that appear in updates posted to Sina Weibo, China”™s version of Twitter, then assigns them to one of roughly 70 “emotional categories.” Those affect the shade and movement of the light, while hexagram symbols from the ancient Chinese text “I Ching” determine the color. For example, at the Sunday launch, the hexagram signifying “water on water” and upbeat emoticons resulted in a light-blue lighting effect, replete with rising peaks and waves corresponding to a majority “happy” population.

“Rhapsody of Light” is not Ms. Ma”™s first project on the Olympic Green. In 2008, she served as one of the seven core creative team members behind the Beijing opening ceremony, an event she now criticizes as “all about happiness and power.”

She and Mr. Zheng, who worked on lighting design for the Bird”™s Nest stadium and other Olympic projects, were commissioned by the government-backed organization that manages the Water Cube, but despite their prior work, they had to convince officials to let them create something that depicts both positive and negative feelings expressed by Chinese people.

“I really had to fight for the right to feel what we feel,” Ms. Ma says.

Mr. Zheng believes that the work taps into an important argument about the use of landmark buildings in China, many of which are designed as bastions of state power. “This is maybe the first landmark building [which] communicates with society,” he says. “Every day it will change its face [according] to the people.”

Still, the results are bound to be skewed, since Weibo posts are routinely censored and deleted. Ms. Ma kept the work”™s overall look and tone abstract, anticipating such activity, and she emphasizes to government officials the “I Ching” aspect over its social-media-influenced one.

She hopes to one day take “Rhapsody of Light” to what she sees as its natural conclusion: a Water Cube display directly controlled by citizens, perhaps via online voting. “If we cannot implement democracy through political means, then art can, in some way,” she says.

“If one day you come here and you don”™t find it beautiful, then ask why it is,” she adds. “I trust that not every day is going to be pleasant and beautiful, but that doesn”™t mean it”™s not meaningful. These are the things which propel us forward for a better future, a better tomorrow.”