Here’s the forty-first installment of LiteratEye, a series found only on The Art of the Prank Blog, by W.J. Elvin III, editor and publisher of FIONA: Mysteries & Curiosities of Literary Fraud & Folly and the LitFraud blog.

LiteratEye #41 – Making a Killing in the Rare Book Business, Texas-Style

By W.J. Elvin III

November 27, 2009

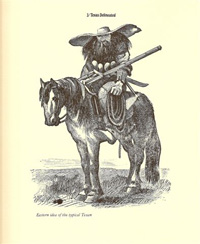

Texans of the old-time cowboy mentality regard stunts like putting an unwary dude on the wildest bucking bronco they can find as just another darn good rip-snortin’ down-home prank.

Texans of the old-time cowboy mentality regard stunts like putting an unwary dude on the wildest bucking bronco they can find as just another darn good rip-snortin’ down-home prank.

And, in that vein, two high-rolling Texas book dealers in this story thought saddling the suckers with forged or stolen rarities was a real knee-slapper.

We’ll get to that but first a bit of background.

Forgery and theft are the two major crime concerns in the rare book business. It’s also a field where, as we shall see, one might just get away with murder.

While forgery is often encountered on the LiteratEye beat, theft also has elements of deception. When selling a stolen rare book the thief will predictably explain: “I found it in an attic.”

Book theft has long appealed to the pros because, for one thing, a small easily-concealed rare book may be worth thousands of dollars, and secondly, until recently book thefts were rarely treated as serious crimes.

Typically, in the recent past, theft of a rare book or document worth thousands of dollars resulted in only a wrist-slap sentence for the culprit – in the unlikely event of capture. You can imagine that as a cop, prosecutor or judge facing today’s chaotic crime situations, it’s kind of hard to get fired up over book theft.

“Send in the SWAT team, we located that missing copy of Newton’s Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica.”

A lady caught in the 1990s in the theft of $1.8-million in rare books was ordered to make restitution of less than $50,000 and sentenced to psychiatric probation. News like that probably irritated the hell out of someone like Leandro Andrade, a three-strikes loser sentenced at about the same time to fifty years to life for stealing $150 in videos.

But times are changing. A participant in a recent crime seminar for collectors, dealers and librarians pointed out that these days “someone who steals a $10,000 book is in fact getting a harsher sentence than someone who steals a $10,000 piece of jewelry, because it is a cultural crime, a crime against citizens.”

To some extent, responsibility for the change in society’s attitude toward book and document theft can be credited to the late John H. Jenkins, a prominent Texas rare book dealer and author of several highly regarded works including a guidebook on security for collectors, dealers and institutions issued in 1982.

Jenkins, then-president of the Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America, also served as chairman of its security committee. He was undoubtedly the far-and-away top rare book dealer in Texas — and claimed to be the biggest in the world, as one might expect of a born and bred Texan. His inventory was at one point put at around $20 million.

Jenkins’ security book helped launch a slow process of at least partial change in the cover-up approach many institutions – colleges and universities as well as museums – took toward discovery of a theft, or discovery of a forgery in their possession.

The traditional rule was to keep it quiet to avoid publicity. News of a theft or forgery could put jobs and public funding at risk, and could discourage donors.

Jenkins was an entertaining storyteller, as I learned reading his Audubon and Other Capers. It’s a tale of his key role in recovery of a very rare edition of Audubon’s famous bird illustrations, the elephant folio.

His efforts in the Audubon case involved playing serious games with mafia mobsters, with not much help from some fairly cavalier FBI agents. How much of it is true, I don’t know. Jenkins was known to ask doubters whether they wanted facts or a good story.

Enter Austin Squatty.

Who? Well, that was Jenkins’ moniker on the high-stakes Las Vegas gambling circuit, where he held forth as a top player. Seems there was a bit more to our man than what met the undiscerning eye. In fact, Jenkins’ perspective on skullduggery in the rare book business undoubtedly owed much to shady personal experience.

That irony is what makes his security booklet one of my personal favorites in the LiteratEye collection.

His inventory, as it turns out, included numerous forgeries and a fair amount of stolen material.

Just as it’s predictable that the thief “found it in an attic,” it is also predictable that a bookseller caught handling a stolen book or forged document “had no idea.”

True, forgers have fooled experts, and the greatest of them is undoubtedly some unknown master of the craft whose work has never been exposed. But Jenkins had a hard time playing stupid when it was noted he was selling forged copies of the very rare, very expensive 1836 Texas Declaration of Independence – over and over again.

At the time of his death — caused by a bullet — Jenkins was under investigation for selling fraudulent documents and suspicion that he played a role in arson at his place of business.

Interestingly, documents destroyed by the fire included heavily insured rarities later shown to be forgeries.

Jenkins was a close associate of rare book dealer Dorman David, a carousing, devil-may-care playboy and heroin addict. For kicks David pulled stunts like driving his sportscar into a drug store to buy a pack of smokes. It’s known, due to his own admissions, that he forged or fabricated numerous famous Texas historical documents.

And it’s suspected that David masterminded a ring of thieves who preyed on courthouses and other sources of historic public documents.

David was the source of some of Jenkins’ best material. Thousands of documents left David’s shop during this time and it appears that many landed in Jenkins’ shop, but everyone associated with the sales has a different story.

As forgeries sold by his gallery were exposed, the ABAA’s ethics committee reluctantly got on Jenkins’ case. He stonewalled his way through the inquiry.

Much of what we now know about Jenkins’ dealings on the dark side owes to the investigative efforts of W. Thomas Taylor, a rare book dealer who got on the case when, in the course of a conversation with another dealer about fakes on the market, he began to suspect that three rare documents he had sold for a total of $85,000 might be David forgeries.

Best-selling author Larry McMurtry, now himself a Texas bookseller, tantalizes us in the introduction to Taylor’s book. McMurtry knew both Jenkins and David, and says “both men were lambs as compared to several of their tutors.” In his own memoirs, McMurtry comes down heavily on Dorman David but takes it easy on John Jenkins.

David eventually got himself unhooked and faced up to the judicial consequences of his crimes.

Jenkins died in 1989. “Whether it was suicide or homicide is still debated,” according to Taylor in his book, Texfake: An Account of the Theft and Forgery of Early Texas Printed Documents.

Authorities in Bastrop, Texas, put Jenkins’ death down as suicide. The case continues to intrigue many of us because, for one thing, he was shot in the back of the head. That’s kind of an unusual approach to suicide.

Another “loose end” is that the weapon with which he allegedly dispatched himself was never found.

photo: Jenkins’ Audubon Caper book

(Copyright 2009 WJE, exclusive to The Art of the Prank, for reprint rights contact Literateye@gmail.com)

Check out previous LiteratEye episodes on The Art of the Prank.