Here’s the fortieth installment of LiteratEye, a series found only on The Art of the Prank Blog, by W.J. Elvin III, editor and publisher of FIONA: Mysteries & Curiosities of Literary Fraud & Folly and the LitFraud blog.

LiteratEye #40: And Death Shall Have No Dominion, Particularly If You’re a Best-Selling Author

By W.J. Elvin III

November 20, 2009

It seems a sad thing that writers who keep on pumping out books after they are dead aren’t around to enjoy the benefits. Maybe there are literary awards passed out in heaven? “Best Book By A Recently-Deceased Author.”

It seems a sad thing that writers who keep on pumping out books after they are dead aren’t around to enjoy the benefits. Maybe there are literary awards passed out in heaven? “Best Book By A Recently-Deceased Author.”

I got to thinking about that after learning that mystery writer and outdoor expert William G. Tapply, who had become just plain “Bill” over the course of our correspondence last year, died recently. He left several books still to be published.

What that leads into is the issue of after-death publishing, not the posthumous publication of completed works as in Tapply’s case but works produced under an author’s name but actually involving other writers.

Sometimes such books are based on partially completed manuscripts, or even derived from ideas jotted on a cocktail napkin. If that.

The issue takes some odd turns.

There’s a ruckus going on in literary circles at the moment over a re-issue of Ernest Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast. The new edition “has been extensively reworked by a grandson who doesn’t like what the original said about his grandmother,” according to a report in The New York Times.

The grandson is of the opinion that the original edition was cobbled together after Hemingway’s death and included a fabricated final chapter. The revised version will be more in tune with his grandfather’s intentions. That’s what he says.

Hemingway biographer A.E. Hotchner, who assisted “Papa” with several literary projects, disagrees.

Hotchner says he personally delivered the completed manuscript of Feast to the publisher at Hemingway’s request, while the author was very much alive. “There was no extra chapter,” according to Hotchner.

Hotchner doesn’t like it that someone can mess with an author’s work after the author is dead.

Sometimes an author’s death means the reading public won’t see any more of his or her work. The author may request any remaining work be destroyed, as did Mark Twain (although his heirs ignored the request, as often happens, after all there’s money to be made in publishing “lost” material).

Or what’s left behind may meet a fate of that of adventurer and translator of erotic tales, Sir Richard Francis Burton. His shocked and appalled wife submitted her finds to the bonfire rather than to a publisher.

Quite a few “discovered” manuscripts by popular authors will be seeing print soon – Vonnegut, Nabokov, Kerouac, to name a few.

Most of what’s coming is described as posthumous publication. Often in such cases the author wasn’t happy with the book and never intended to send it off. But it happens that someone who later finds the manuscript believes it to be of literary value, or, as mentioned, in the case of some heirs, believes it to be at least good for a fistful of dollars.

Publishers are inclined to look at rolling the presses using a dead author’s name as branding. The author’s name becomes a trademark term. Actually, that goes on with living authors as well as dead. If an author’s name guarantees readership, why not put it on the book regardless of who wrote it?

It’s a practice with a long history, easily dating back to the books of the Bible, and certainly to Greek and Roman historians, philosophers and poets.

And today?

Gothic horror author V.C. Andrews (Flowers in the Attic) wrote a number of popular novels while alive and has since added 33 more.

Thriller writer Robert Ludlum continues to crank out the bestsellers despite current residence in the cold, cold ground.

Isaac Asimov, a veritable book factory while alive, manages to publish successfully from the grave with the aid of posthumous collaborators.

Michael Crichton died last year. His new book is due out this month, Pirate Latitudes. It was rumored to be an unfinished historical novel found in his files, but the publisher says it wasn’t doctored — it was complete when discovered. Maybe the rumor refers to a second forthcoming book by Crichton, title unknown at present.

Novelists David Foster Wallace and Roberto Bolano left behind unfinished work that is being polished for future publication. At least in Bolano’s case, it is known that he produced the manuscripts while his health failed, wanting to provide for his family in the future.

Ralph Ellison’s Juneteenth novel was a 2,000-page manuscript when he died. His biographer, John Callahan, edited it down to 368 pages for release by Random House, according to a report in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

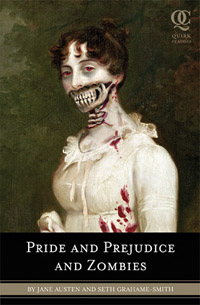

Interestingly, it is apparently within the rules of the game to team up with a dead author, once copyright restrictions have expired. An example is Pride and Prejudice and Zombies by Jane Austen and Seth Grahame-Smith.

No permission was needed to use Austen’s name. On some book review sites it’s discussed as a moral issue. “Shame, shame, for using Austen’s name as co-author.” That sort of thing.

Well, really? If I shared the byline of this column with, say, Edgar Allan Poe, you’re smart enough to know I’m up to something artsy, or at least crafty. To me, it only becomes a moral issue if I try to interest you in a Poe manuscript I found recently in granny’s attic – found it the day after I forged it, of course.

One of the most interesting invitations to collaborate is Charles Dickens’ The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Dickens left the novel unfinished and writers since have profited by offering up their own conclusions.

The Last Dickens by Matthew Pearl is the latest in that line, issued last month. Pearl isn’t in the category with those who simply add their touches to an unfinished work, though. He weaves a spell-binding tale around the disappearance of the final chapters of Drood.

Sharing a byline with a deceased author may be a bit much, but it’s not at all unusual for an author to rework a tale told by another author, since deceased. Shakespeare is often offered up as an example of authors who made substantial use of the work of previous authors. And, Lord knows, enough authors since his day have made use of Shakespeare’s creations.

One particularly bizarre niche in the area of dead writers who won’t stop writing regards those who channel their later works from the spirit world. In pursuit of examples, I tracked down a copy of Shakespeare’s Revelations By Shakespeare’s Spirit, published in 1919. The Bard communicated his recent work to medium Sarah Taylor Shatford.

Shakespeare provided a forward to the book, and then a hundred or more “sonnets” on topics mainly romantic or spiritual. To that he added a number of fairly trite aphorisms, peculiar observations, and essays on metaphysical topics.

The channeled Bard is revealed as a man of some ugly prejudices who had opinions on topics ranging from psychoanalysis to aerial combat. There are some indications that he may have lost touch with his muse over the course of the passing years. There are lines that leave you scratching your head: “Hang up your beaver and pay the compliment of chatting awhile.”

One other case of channeling comes to mind. As those who’ve followed the column for a while know, not so long ago I was trying to locate the author of the bogus James Dean poems. The poetry, allegedly channeled to a (non-existent) Carlton Hayes, turned out to be the work of Stephen R. Pastore, a writer who fakes reviews of his own books and provides his own literary awards.

Not so long ago Pastore left Scranton, PA, for parts unknown. It was rumored he was headed for Provence, but it turns out he only moved as far as Sandwich, MA, where he’s submitting rants to the local newspaper and organizing a writers group.

Lisa Marie Payne, head of one of the James Dean fan clubs, is among those who condemns the disservice to readers committed in concocting poems in Dean’s name. She told me Dean did actually write poetry, and I searched far and wide for examples without success.

Payne recommended contacting Dean biographer David Loehr, who could provide examples. Loehr, like Pastore, hasn’t answered my emails.

I haven’t tried channeling either of them.

But I suppose that only works with the dead. With the living, one uses telepathy. Now, I wonder, if Dan Brown were to dictate a book to me telepathically, could I publish it as a collaborative effort?

photo: amazon.com

(Copyright 2009 WJE, exclusive to The Art of the Prank, for reprint rights contact Literateye@gmail.com)

Check out previous LiteratEye episodes on The Art of the Prank.