The Science of Magic: Not Just Hocus-Pocus

CBSnews.com

November 1, 2009

Neuroscientists and Magicians Are Studying How Sleight of Hand Affects the Brain, and Its Potential to Diagnose Autism

Las Vegas can be a magical place. It certainly is for Penn and Teller, who have been performing magic in their own Las Vegas theatre for almost eight years.

Las Vegas can be a magical place. It certainly is for Penn and Teller, who have been performing magic in their own Las Vegas theatre for almost eight years.

The house is packed every night – a testament to both Penn and Teller’s draw . . . and to the universal appeal of magic itself.

“What makes for a successful trick?” Blackstone asked Teller, who never says a word on stage. He broke his silence for our interview (but insisted that we not show his moving lips).

“The core of a successful trick is an interesting and beautiful idea,” he said, “that taps into something that you would like to have happen. One of the things we do in our live show is I squeeze handfuls of water and they turn into cascades of money. That’s an interesting and beautiful idea.

“The deception is really secondary,” Teller said. “The idea is first, because the idea needs to capture your imagination.”

“Magic does something really that no other kind of performing art can do, and that is, it manipulates the here and now – our reality,” said Noel Daniel of Taschen Books in Los Angeles. She has just edited a book on the history of magic, “Magic 1400s-1950s.”

“When we’re watching a movie, we don’t think that what we’re watching is real; we know it’s not,” said Daniel. “We’re staring in a dark room, at a lit screen. But in magic, we’re watching someone manipulate a coin, or cards, or fire, or sawing a woman in half, right on stage, in front of our very eyes. And this is the power of magic.”

Daniel spent over a year compiling old, rare images of magic through the ages.

She says the first magic performance is thought to have been in Egypt around 2000 B.C.: A shaman proving his powers to the pharoah.

“He took a duck, decapitated its head, and then restored the head to the living animal,” said Daniel. “Of course, this impressed the king very much!”

But the impression made by magicians has not always been as positive.

During the Middle Ages in Europe, they were sometimes accused of witchcraft, and were banned from certain towns. Only by the late 16th century did suspicion give way to applause, as magic assumed its place among the performing arts.

For centuries to follow, crowds would watch in wonder, consumed by a question that still resonates today:

“How does the magician get the audience member to believe? And that’s where the magic takes place,” said Daniel.

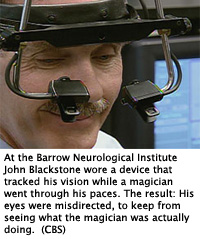

How magic works – and why we keep falling under its spell – is now the subject of some serious investigation . . . not in a magician’s workshop, but at a leading center for neurological research, the Barrow Neurological Institute in Phoenix, Ariz.

There, two Harvard-educated neuroscientists came to the humbling realization that magicians sometimes understand the mysterious workings of the human brain more than they do.

“The more we thought about it, the more we realized that magicians actually had skills that we didn’t have, as scientists,” said Dr. Stephen Macknik.

Dr. Susana Martinez-Conde said what they are trying to get at is “why the tricks work in the mind of the spectator, and what are the brain principles behind it.”

So in the interest of neuroscience the two researchers have been collaborating with several magicians, including Teller.

Read the rest of this article here.