Asian Pop: Candy-coated chaos

by Jeff Yang

SF Gate

July 1, 2009

Fake cooking show with puppets in a surreal cartoon landscape? It’s IFC’s ‘Food Party.’

On a rainy, otherwise miserable day in Brooklyn, N.Y., Thu Tran is happily contemplating Jell-O.

On a rainy, otherwise miserable day in Brooklyn, N.Y., Thu Tran is happily contemplating Jell-O.

Ever since the June 9 debut of her deliciously weird series “Food Party,” a series of hilarious 10-minute shorts that airs as part of the Independent Film Channel’s four-hour “Automat” block of music, comedy and animation (Tuesdays, 10 p.m.), Tran has been inundated with requests to participate in food-related activities. Today, she’s preparing to serve as celebrity judge for a local gelatin-mold design competition.

“We’re judging entries based on visual appeal, structural integrity and also, edibility,” she says, although she admits the last category is probably the least important of the three, which makes the event one that plays to Tran’s strengths — it’s about food as art, rather than the art of food.

Besides, as a Vietnamese American from Cleveland, Ohio, Jell-O and Jell-O analogues played a profound role in Tran’s upbringing.

“In Cleveland, Jell-O is basically the fifth food group,” says Dan Baxter, Tran’s longtime boyfriend and partner-in-crime. “Everyone eats it, even Thu’s family. We had it the last time I visited her house, although I’m not sure that was Jell-O, exactly.”

“It was agar-agar,” corrects Tran. “Same thing, only made of seaweed.”

Thu the extreme

Jell-O is an apt metaphor for the brilliantly bizarre “Food Party.” America’s favorite dessert appears to be a cool pile of sweet, wiggly neon, but it hides a stomach-churning secret — it’s made from a horrifying slurry of chopped and boiled animal cadavers.

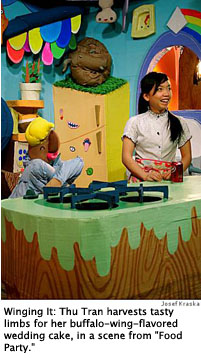

Similarly, on its surface, “Food Party” is a friendly, pastel-colored confection, a fake cooking show in which Tran interacts with fanciful puppets hand-crafted by Baxter in a surreal cartoon landscape, but a darker and far more adult reality lurks beneath these saccharine visuals.

When Tran sends out wedding invitations in the show’s premiere episode, she stands by a papier-mache window and shouts, “Birds of the world, come to me!”, summoning a Snow White-style cloud of puppet avians. After they do their delivery chores, they lovingly return to Tran for their promised reward: A night in her luxurious four-star Bird Hotel, which is quickly revealed instead to be a machine that severs and harvests the birds’ savory limbs.

“Birds are kind of dumb,” notes Tran brightly to the camera, as she proceeds to use the wings to make a “very lovingly desired wedding cake that is buffalo-wing flavored!”

Putting “gross” into engrossing

If “Food Party” sounds disturbing, that’s because it is. It’s also the most compelling short-form television you’ll watch this year, channeling the funniest and nastiest aspects of shows like “South Park” (which shares its lo-fi aesthetic and not-for-kids kiddie-show angle) while taking well-aimed potshots at the sitting duck-a-l’orange known as Food TV.

“Food Party” doesn’t really teach you how to cook (unless you have an appetite for “cave duck flesh” or “green screen cookies“). Then again, neither do most cooking shows.

“No one watches Food Network to learn how to cook — they’re just obsessed with looking at and thinking about food,” says Tran. “I mean, people don’t watch pornography to learn how to have sex.”

Make no mistake, as strange and funny as it is, “Food Party” is as obsessed with cuisine as its glossier cable counterpart.

Food is at the center of the “Food Party” universe — in fact, food is a good portion of that universe, given that the show’s cast includes recurring characters like the horny lounge-lizard Ice Cream Cone and smooth-talking, Gauloise-smoking Monsieur Baguette.

“I’m Vietnamese, so food has always been a focal point for my family,” says Tran. “It’s all any of us ever talks about. At family gatherings, we have these huge meals, and we just sit there all night, eating and commenting about the food.”

Tran’s parents

Tran says her father is the main cook in their family, and cites him as her primary creative influence, both in terms of his love for food and his somewhat twisted sense of humor.

“My dad was always cooking really, really crazy stuff,” she says. “He always takes pride in the element of surprise — he’ll cook this delicious dish and be like, ‘Can you guess what meat that is?’ And we’ll be like, ‘It’s not beef?’ ‘No.’ ‘Pork?’ ‘No.’ ‘Uhh … is it … cat?’ He has hunting buddies who’ll just go kill stuff and bring it home for him to cook.”

Tran recalls one meal in particular. “When I was growing up, there was this little bird’s nest sitting on the windowsill outside of our kitchen,” she says. “One morning, we came down to breakfast, and there was bacon and toast, and these tiny sunny-side up eggs, the size of quarters. And we were like, ‘Dad, where’d you get these?’ And he just laughed and laughed, like it was this great joke that he’d stolen all of this poor little bird’s eggs.”

Not that Mr. Tran was being malicious with his prank. “Humor is a way to connect with stuff you might otherwise be uncomfortable dealing with” — like the fact that food in many cultures is less a gourmet experience than a matter of subsistence, forcing you to eat whatever you have at hand to survive.

“I mean, when my parents left Vietnam, my dad kept it a secret from my mom they were going,” says Tran. “And now, she thinks that whole crazy episode is just hilarious. ‘Thu, your dad tricked me! I couldn’t even say goodbye to my mom or my dad or my sisters! I was pregnant with you, and we had to leave your brother behind! They had to mail him to us in the United States later! Hahahahaha.'”

Party of Thu

As you watch “Food Party,” you might find yourself wondering who in their right mind would develop a show like this for television. The answer, of course, is no one.

This version of “Food Party” is actually its third incarnation: It began as a mixed-media piece Tran created for a solo art show, before she decided to immortalize the installation — “I realized it was not mobile, and I couldn’t afford to store it after graduation” — by using it as the set for a “bootleg” video.

That video became the first in a series of “Food Party” webisodes, featuring Tran pretending to cook meals for last-minute celebrity drop-ins, like Jay-Z and Beyonce; the guests, like most of the cast other than Tran, were represented with crude puppets, built by Baxter and animated by Tran’s Art Institute friends.

Uploaded to YouTube, the webisodes quickly drew a cult following; upon being discovered by New York Magazine, it attracted the attention of cable channel IFC, which signed Tran to a six-episode TV commitment, and which, based on the show’s critical acclaim and growing fan following, they seem certain to extend. After all, the show is astoundingly cheap to produce and incredibly addictive.

Kind of like Jell-O. And, as they say — there’s always room for Jell-O.

PopMail

“Food Party” is a classic example of new technology enabling original, authentic, and yes, eccentric talents to end-run the system, providing an alternative path for voices from traditionally overlooked communities — like Asian America — to gain mainstream attention.

I followed Thu to the Gowanus Jell-O Mold Competition to check out the cool and unusual gelatin creations local artists had come up with, things like a Jell-O turkey stuffed with Jell-O; Jell-O bling set with Jell-O gems and a Carmen Miranda fruit-basket hat made entirely out of Jell-O.

As I looked at the array of innovative sculptures, jiggling in the light breeze from the studio space’s doorway, it struck me that Jell-O (quite a resilient metaphor, that) could also serve as an illustration of the opportunities and pitfalls of user-generated content.

Platforms like YouTube have made media creation accessible to the masses the way that Jell-O made dessert creation accessible: Instant, inexpensive, simple, universal.

If you just dump the box in a bowl, you get something that’s visually uninteresting and nutritionally empty — junk food. With a little effort and inspiration, however, you can make something like “Food Party” or the sculpted works in the Jell-O competition … weird, beautiful, subversive art.

In short, just because it’s easy to put stuff up online doesn’t mean you should put stuff up online that’s easy to make; I wish more creators would realize that Web content can be as complex, considered and innovative as any other artform, and push their own limits, and that of the medium itself.

One last funny note: When I first read that the person behind “Food Party” was “Thu Tran,” I was puzzled; I’d just gotten some e-mail from a friend, Bay Area foodie Thy Tran, and she hadn’t mentioned anything about a new cable series.

Then I did a doubletake, noting the spelling was off by a letter, and realized that this was another case of Asians Just Don’t Have Enough Names to Go Around syndrome.

I mentioned it to Thy, and she laughed and noted I was far from alone in making that mistake: “I’ve received e-mails congratulating me and commiserating that the New York Times misspelled my name. Hilarious!”

So: Thu Tran, “Food Party” host, and Thy Tran, “Bay Area Bites” blogger and Asian Culinary Forum founder/director are not the same person. Got that? Good.

Jeff Yang forecasts global consumer trends for the market-research company Iconoculture (www.iconoculture.com). He is the author of “Once Upon a Time in China: A Guide to the Cinemas of Hong Kong, Taiwan and Mainland China,” co-author of “I Am Jackie Chan: My Life in Action” and “Eastern Standard Time,” and editor of the forthcoming “Secret Identities: The Asian American Superhero Anthology” (www.secretidentities.org).