[Ed. note: Author Paul Maliszewski published an interview with Joey Skaggs in McSweeney’s, Volume #8, August 2002.]

Michael Dirda on “Fakers”

by Michael Dirda

The Washington Post

January 18, 2009

The Madoffs of the world tell us what we want to hear.

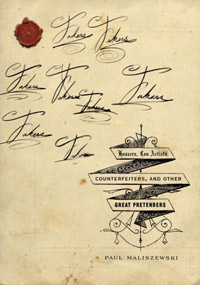

Fakers: Hoaxers, Con Artists, Counterfeiters, and Other Great Pretenders

Fakers: Hoaxers, Con Artists, Counterfeiters, and Other Great Pretenders, By Paul Maliszewski, New Press. 245 pp. $24.95

Paul Maliszewski grew interested in the psychology of faking and forgery when he worked as a young journalist for a small business magazine. Bored, he began to send in letters to the editor under various pseudonyms. These letters, commenting on recent articles, were sly exercises in satire and humor. For example, when the Dow fell in 1997 “Gary Pike” wrote in to describe how he had been “listening” to the Dow, but until one day “I called and called, but the Dow said nothing in return, answering only in silence.” As Maliszewski clearly knows, the Tao of Asian philosophy is pronounced Dow, and in a famous phrase “The Tao is Silent.”

Building on his personal experience with hoaxing, Maliszewski gradually began to publish articles — in the Baffler, McSweeney’s and Bookforum, among other periodicals — about the nature, variety and meaning of modern fakery. Collected here, these pieces cover the phony journalism of Jayson Blair of the New York Times and Stephen Glass of the New Republic; the whole-cloth memoirs of James Frey; the art forgeries of Elmyr de Hory and Han van Meegeren; the provocations of conceptual artists like Sandow Birk (who created a series of “historical” paintings about a supposed war between Northern and Southern California) and Joey Skaggs (who constructed an elaborate website for a nonexistent organization promoting cemeteries designed to resemble theme parks); brief histories of some imaginary poets and their work (the Spectra hoax and the Ern Malley affair); and, finally, novelist Michael Chabon’s “fictional” memoir about his childhood encounter with a Holocaust survivor who turned out to be a Nazi soldier, only who wasn’t since he didn’t really exist.

While Maliszewski does talk to a number of the fakers he discusses, for the most part he acknowledges that others before him have done the primary sleuthing. His own essays and interviews are not so much potted versions of sometimes familiar stories as attempts to understand the psychology of deception. Why are we so readily duped? The short answer is that con games confirm what we already want to believe. The made-up news stories and fudged memoirs fit certain “forms,” as Maliszewski calls them: “Fictional journalism is essentially a careful imitation of journalistic forms. That is, the articles are convincing because they adhere closely to the unstated conventions, assumptions, and predilections of a particular publication, a particular kind of article, or a particular editor. Journalists who fake are extraordinarily sensitive to the ways in which their stories are a series of sometimes conventional, often routine forms.”

Fakers derive their power from our own expectations and prejudices. Stephen Glass’s talent, writes Maliszewski, “lay less in the originality of his imagination than in his solicitous ability to seize on whatever the conventionally wise were chatting about at cocktail parties and repackage it in bright new containers, selling the palaver right back to them. Nobody was the wiser.” Studied more closely, though, Glass’s “wild inventions form a thin skin stretched over a fairly standard body of accepted truth and mainstream opinion. Glass’s imagination is not, in other words, all that original. It is, in fact, crushingly banal. How else to explain his production of so many fabrications that deliver, in story after story, the shared assumptions of the editorial class in new and perhaps slightly surprising forms?”

Shared assumptions is a key. Back in 1916, the work of the imaginary “Emanuel Morgan” and “Anne Knish” — the leading figures in the so-called “Spectra” school of poetry — was instantly taken to be cutting edge, echt modern, the latest thing. In fact, the Spectra poems were doggerel, created by the traditionalist poets Witter Bynner and Arthur Davison Ficke to mock the free verse of such movements as imagism and vorticism. Spectra, says Maliszewski, elegantly “demonstrates that any new writing, from reporting to reviewing to intellectual journalism, finds the easiest path to publication by seeking the consensus and falling into the deep groove of what’s already written and held to be true.” Everyone knows that if it’s incomprehensible, then it must be avant-garde poetry. The more incomprehensible, the better the poetry.

The shrewd faker fulfills the needs of his audience. When conceptual artist Joey Skaggs fielded questions from reporters about his fake website, “I made up answers I thought they’d like.” He adds that “my experience has shown me that most journalists don’t want to screw up a good story with reality, and they will talk themselves out of questioning the story to death.” As the saying goes, some stories are too good to check.

What fakers do, then, is simplify complexities; they feed our secret prejudices and beliefs. This is one reason why many forged Old Masters look so ludicrous a generation or two after they were created: The forgeries reflect, and often overemphasize, the artistic beliefs of their own time about earlier works. Van Meegeren’s knock-offs of Vermeer are designed to match the dreams and theories of 1930s art scholars. They are pastiches, and soon begin to look it.

The same is true of fake newspaper articles. These tell us the stories we want to hear, rather than the stories that are really out there. As a result, emphasizes Maliszewski, they damage serious work, for “there are articles — real articles, these, about true subjects — that cannot be easily written or are not practical to publish simply because they don’t fit one of the accepted forms.”

While Fakers is certainly entertaining and thoughtful, it nonetheless remains a hit-skip collection of articles rather than a sustained narrative. Fakery cries out for even more attention. After all, so much of modern life and culture is sham and ersatz. Ours is a world of public relations spin and post-modern irony, of staged “reality” shows and the smoke and mirrors of corporate bookkeeping and political double-talk. Is it real or is it Memorex? Does it matter? Is modern-day wrestling fake when we know that it’s as choreographed as a Balanchine ballet? We love movies about elaborate cons and capers (“The Sting”), as well as those that deliberately trick the viewer, such as “The Sixth Sense,” “House of Numbers” and “The Spanish Prisoner.” Everyone’s favorite science fiction novelist, Philip K. Dick, obsessed constantly about the difficulty of distinguishing the human from the replicant, the authentic from the imitation. Because of weapons of mass destruction that didn’t exist, because of imaginary connections with 9/11 terrorism, we invaded Iraq. There’s a little in Fakers about the Enron scandal, but obviously nothing about the alleged Ponzi schemes of Bernard Madoff. Given the experience of just the last few years, Maliszewski will never run out of fresh material.

At the heart of fakery lies the same impulse that makes art: design. As Maliszewski says, “life is an unedited mess. Life is so many spools of raw videotape, a long and winding transcript preserving every ‘uh,’ ‘um,’ and ‘oh.’ Life, were it like a movie, painfully lacks dramatic arcs.” But a news story or a book requires those dramatic arcs, needs some kind of theme, focus or organizational principle to make it readable. It’s not by accident that the modern memoir — that most fudgeable of forms — often follows the same pattern as the 17th-century spiritual autobiography: I was a horrible sinner, I saw the light, and I have now come forward to testify to my redemption and be an example to others. As Maliszewski notes: “Our fakers are believed — and, at least for a time, celebrated — because they each promise us, screen-gazing and experience-starved, something real and authentic.” That siren-song allure of the real and authentic still gets us every time. We’re all suckers for a good story, especially one that, according to the slang phrase, “tells it like it is” — or rather how we imagine it must be.