Elusive Forger, Giving but Never Stealing

By Randy Kennedy

The New York Times

January 11, 2011

His real name is Mark A. Landis, and he is a lifelong painter and former gallery owner. But when he paid a visit to the Paul and Lulu Hilliard University Art Museum in Lafayette, La., last September, he seemed more like a character sprung from a Southern Gothic novel.

His real name is Mark A. Landis, and he is a lifelong painter and former gallery owner. But when he paid a visit to the Paul and Lulu Hilliard University Art Museum in Lafayette, La., last September, he seemed more like a character sprung from a Southern Gothic novel.

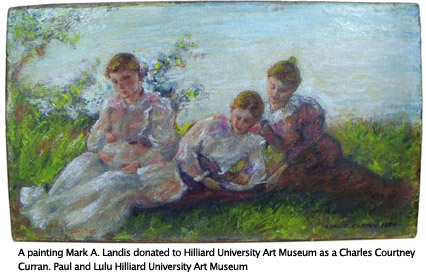

He arrived in a big red Cadillac and introduced himself as Father Arthur Scott. Mark Tullos Jr., the museum”™s director, remembers that he was dressed “in black slacks, a black jacket, a black shirt with the clerical collar and he was wearing a Jesuit pin on his lapel.” Partly because he was a man of the cloth and partly because he was bearing a generous gift “” a small painting by the American Impressionist Charles Courtney Curran, which he said he wanted to donate in memory of his mother, a Lafayette native “” it was difficult not to take him at his word, Mr. Tullos said.

The painting, unframed and wrapped in cellophane, looked like the real thing, with a faded label on the verso from a long-defunct gallery in Manhattan. Father Scott offered to pay for a good frame and hinted that more paintings and perhaps some money might come the museum”™s way from his family. But when the Hilliard”™s director of development chatted with Father Scott about the church and his acquaintances in deeply Roman Catholic southern Louisiana, the man grew nervous. “He said, “˜Well, I travel a lot,”™ “ Mr. Tullos recalled. ” “˜I go and solve problems for the church.”™ “

Mr. Landis “” often under his own name, though more recently as Father Scott or as a collector named Steven Gardiner “” has indeed done a lot of traveling over the past two decades, but not for the church. He has been one of the most prolific forgers American museums have encountered in years, writing, calling and presenting himself at their doors, where he tells well-concocted stories about his family”™s collection and donates small, expertly faked works, sometimes in honor of nonexistent relatives.

Unlike most forgers, he does not seem to be in it for the money, but for a kind of satisfaction at seeing his works accepted as authentic. He takes nothing more in return for them than an occasional lunch or a few tchotchkes from the gift shop. He turns down tax write-off forms, and it”™s unclear whether he has broken any laws. But his activities have nonetheless cost museums, which have had to pay for analysis of the works, for research to figure out if more of his fakes are hiding in their collections and for legal advice. (The Hilliard said it discovered the forgery within hours, using a microscope to find a printed template beneath the paint.)

In the weeks since an article in The Art Newspaper first revealed the scope of the forgeries, museums and their lawyers have been trying to locate Mr. Landis, who was never easy to find in the first place because he often provided bogus addresses and phone numbers. But now he seems to have disappeared altogether. His last known attempt to pass off a forgery occurred in mid-November, when he presented himself, again as Father Arthur Scott, at the Ackland Art Museum at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, bearing a French Academic drawing.

“It”™s the most bizarre thing I”™ve ever come across,” said Matthew Leininger, the director of museum services at the Cincinnati Art Museum, who first met Mr. Landis in 2007 when Mr. Leininger was the registrar at the Oklahoma City Museum of Art, and Mr. Landis offered to donate several works under his own name.

In the years since, Mr. Leininger has appointed himself as a kind of Javert to Mr. Landis”™s Valjean. He maintains a database of all known contacts with Mr. Landis, sightings of him and works he has copied. (He tends to favor lesser-known artists but occasionally tries his hand at a Picasso, a Watteau or a Daumier.) Mr. Leininger circulates by e-mail a picture taken of Mr. Landis in 2008 by the Louisiana State University Museum of Art, and he uses a dry-erase marker to update a laminated map in his office.

The first donation Mr. Leininger has been able to find was to the New Orleans Museum of Art in 1987. He has charted Mr. Landis”™s travels to 19 states and his contacts, either in person or by phone or letter, with more than 40 museums since then, including large institutions like the National Portrait Gallery in Washington and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Not all of the museums have accepted Mr. Landis”™s donations, but many have, and some have displayed them as authentic works. While some examine donations as a matter of course, others did so only after growing suspicious of Mr. Landis. The St. Louis University Museum of Art still lists his donations on its Web site but describes them as in the “manner of” Stanislas Lepine and Paul Signac, not as works by the artists.

George Bassi, the director of the Lauren Rogers Museum of Art in Laurel, Miss., where Mr. Landis, 55, has lived off and on for years, said he first encountered him eight years ago, after Mr. Landis moved back to the South from San Francisco, where he is believed to have owned a small art gallery.

Mr. Bassi knew Mr. Landis”™s mother, Jonita Joyce Brantley, who was born and raised in Laurel and was a member of the museum. (She died last April.) When Mr. Landis contacted the museum and said he wanted to donate artworks in his father”™s memory, Mr. Bassi said his story seemed to add up at first.

“He had a connection to Laurel and he knew of the museum,” he said, “and you just assume good intentions.”

“But then you could never contact him. None of his numbers worked. You had to rely on him stopping by the museum, without an appointment. And you could go six months without seeing him.” The museum”™s suspicions aroused, it examined the works and determined they were forgeries.

On the advice of lawyers, it did not explicitly warn other museums about its discoveries, Mr. Bassi said, but it tried to let them know to be wary of donations from a Mark Landis.

“I don”™t think his mother had even a clue that this was going on,” he added. “And she was such a sweet lady, and that made it that much harder for us to talk to people about this and tell them what we thought he was doing.”

Numerous attempts to contact Mr. Landis at phone numbers listed for him in public records and at numbers he provided to museums were unsuccessful. Robert K. Wittman, a former F.B.I. agent who ran the agency”™s art-crime team, said that he has been working informally on behalf of several museums Mr. Landis visited to gather more information about his actions, with the aim of determining whether a legal case could be built against him for theft of goods and services. But Mr. Wittman has been unable to find him.

Mr. Tullos of the Hilliard said his museum “would like to find a way to stop him” in case Mr. Landis decided to adopt another identity and keep up his campaign. “He”™s very well read and knows a lot about art history, and so he can be very convincing,” he said. “He”™s a pistol.”

“But I really doubt that there”™s going to be any will or funding to pursue action against him, which is kind of sad,” he added. “That”™s just the reality. So our job now is to make sure that every museum out there knows what he looks like and what he”™s up to.”