A comprehensive, although theoretical, exhibition of the history of Alfred E. Newman, Alfred, We Hardly Knew Thee! continues through Feb. 7 in the Ford Gallery in Ford Hall at Eastern Michigan University in Ypsilanti. Ford Hall is north of Cross Street at the intersection of Normal Street. Gallery hours are 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Mon. and Thursday.; 10 a.m. to 7 p.m. Tuesday and Wednesday, and 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. Friday and Saturday. Closed Sunday. Information: 734-487-0465.

Mad for Alfred:

A new exhibit shows Mad magazine’s poster boy has a shadowy past

by Tahree Lane

The Toledo Blade

January 20, 2008

Mad magazine’s lovable poster boy is as emblematic of the last half of the 20th century as any cartoon character.

Mad magazine’s lovable poster boy is as emblematic of the last half of the 20th century as any cartoon character.

But the face we know as Alfred E. Neuman has a storied past that reaches back 200 years and has its roots in discrimination.

“The image is fluid and flexible and has been with us from George Washington to W. Bush,” says John E. Hett, publisher of the intermittent The Journal of Madness.

An avid collector of all-things-Mad, Hett has loaned his theories on Alfred’s Irish origins as well as most of the 200-plus items in the exhibit, “Alfred We Hardly Knew Thee!” on view through Feb. 7 in the Ford Gallery at Eastern Michigan University in Ypsilanti.

An avid collector of all-things-Mad, Hett has loaned his theories on Alfred’s Irish origins as well as most of the 200-plus items in the exhibit, “Alfred We Hardly Knew Thee!” on view through Feb. 7 in the Ford Gallery at Eastern Michigan University in Ypsilanti.

For comic fans, a rare highlight will be at 7:30 p.m. Wednesday in EMU’s Halle Library Auditorium, when Hett, 44, will be joined at a free lecture, slide show, and reception by 82-year-old Al Feldstein, Mad’s editor from 1956 to 1984. The exhibit will be open before and after their talks.

Popular mass-media characters survive by changing, says Hett, citing the best-known of all – St. Nicholas, a humble Greek saint who morphed into a jolly round Santa Claus created for Coca-Cola advertisements in the early 1930s.

Popular mass-media characters survive by changing, says Hett, citing the best-known of all – St. Nicholas, a humble Greek saint who morphed into a jolly round Santa Claus created for Coca-Cola advertisements in the early 1930s.

The exhibit is split between Alfred’s ancestors, some bearing more obvious resemblances than others, and his 54 charmed years as the face of Mad.

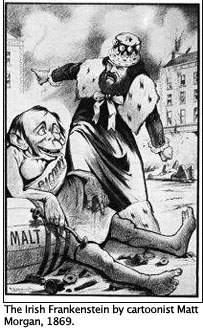

It opens with caricatures of the Irish portrayed as ape-faced “Paddys” and “Bridgets” in American and English magazines. At various points in time, the Irish were depicted as menacing terrorists hell-bent on sovereignty for Ireland, lazy drunks with too many kids, immigrants blindly loyal to the Pope and the Nationalist Movement back home, or – and this is Alfred’s most direct ancestor – carefree and oblivious.

“Today, what we consider offensive, at that time was perfectly acceptable,” said Richard Rubenfeld, EMU art professor and an exhibit curator, along with Hett and gallery director Larry Newhouse.

“Today, what we consider offensive, at that time was perfectly acceptable,” said Richard Rubenfeld, EMU art professor and an exhibit curator, along with Hett and gallery director Larry Newhouse.

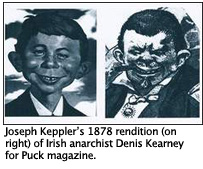

During a time when African-Americans, Chinese-Americans, and Native Americans were equally derided, the Irish were spoofed by top illustrators of the 1800s, including Thomas Nast, Frederick Opper, and Joseph Keppler.

These uncouth monkey-folk actually suggest Alfred with their broad, goofy grins and massive ears perpendicular to the head. One sketch shows a chap washing his feet in a public drinking fountain; another, by Thomas Nast, entitled “The Day We Celebrate: St. Patrick’s Day, 1867,” has a bunch of drunken monkey-men wearing top hats and suits, savagely beating police with jagged chair legs.

In the late 1880s, Frederick Opper streamlined the character into a very Alfred-esque boy playing with a pistol.

By 1900, the fruits on the family tree are decidedly Alfred. In newspaper ads, his grin features a missing tooth and he proclaims the extraction to have been painless, thanks to a new medicine.

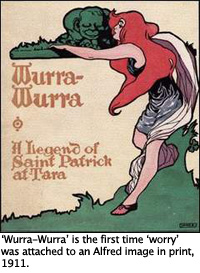

Hett theorizes that the image’s association with worry (as in Alfred’s motto, “What Me Worry?”) dates to a 1911 book, Wurra-Wurra: A Legend of Saint Patrick at Tara, a satirical tale of how the Irish joined worry societies at which they prayed to their Wurra-Wurra god. Irish immigrants often muttered something that sounded like “wurra-wurra” but actually was a Gaelic plea to the Blessed Virgin Mary, he said.

“I think it’s very plausible,” said Hett of the worry connection.

A 1914 poster of a dead-on Alfred includes the words “Me Worry?” Sixty years later, it was the basis for a copyright-infringement lawsuit against Mad; Mad, pointing to the early dentistry ads, prevailed.

Alfred’s happy mug started turning up all over the place: on matchbooks, ads for beer, bars, and cleaning products. In 1930, it appeared in a University of Minnesota yearbook supplement.

During 1936 and 1940 presidential campaigns, Alfred look-alikes were printed on anti-Franklin D. Roosevelt posters and postcards with phrases such as, “Sure I’m for Roosevelt” and “Me Worry?” And for the unending effort to raise money for World War II, five Alfred images, including two females, were printed on envelopes with patriotic comments about various branches of the service: “Me worry? H— no! I’m gonna join the Waves,” notes one.

The first to bear “What me worry?” is a card with a female Alfred, postmarked 1946.

And in 1947, Alfred’s western cousin, Howdy Doody, became the first network children’s show to run five days a week.

Mad’s first editor, Harvey Kurtzman, used a little Alfred image on the cover of a 1954 anthology, The Mad Reader, and again, as a dime-sized face in a border around the July, 1955 cover.

“Harvey began to play with him a little but he didn’t decide to use him as a logo,” said Al Feldstein, who became Mad’s hardworking editor in 1956.

Mad had made the transition from comic to magazine by then, and Feldstein figured it needed a personable mascot along the lines of Betty Crocker, Uncle Ben, the Jolly Green Giant, and the Smith Brothers. He liked the image Kurtzman had used and hired illustrator Norman Mingo to paint a definitive portrait for the cover of the December, 1956, issue, in which Alfred E. Neuman appears for the first time, and, no less than as a write-in candidate for president.

The moniker itself was a pen name the prolific Feldstein had used when he published multiple stories in one magazine.

He figures that young people, especially males, identified with Alfred’s way of laughing at life at a time when the national mood was darkened by a Cold War with a frightening enemy.

“Teen boys were using Mad as an orientation into the adult world,” said Feldstein. “At a time of insecurity and fear of total annihilation from a Cold War blow up, Alfred was appealing as a kind of a victim of the machinations of politicians and industry, and the Cold War that was draining our economy,” he said in a telephone interview from his 270-acre ranch in Montana, where he paints landscapes. Alfred was a bipartisan Everyman, skewering politicians of all stripes.

“No matter how bad the world was around him, he was going to laugh it off and see the humor in it.”

Feldstein admires Hett’s research of Alfred’s family tree.

“I think it’s a fantastic history of Mad and Alfred E. Neuman’s popularity,” he said. “I think some of his examples might be a little creative.”

Mad’s circulation peaked in 1974 with eight annual issues averaging sales of 2.13 million, said Hett. It’s now a monthly with a circulation of less than 200,000 per issue. Alfred has appeared on the cover of almost all of its 480 issues.

The EMU exhibit spills out of the Ford Gallery and into the hall, displaying all kinds of Mad paraphernalia, including a straight jacket, prank squirt guns in the form of a stapler and a watch, $3 bills, car ads, patches, puppets, Mad magazines in many languages (including Turkish and Finnish), and a poster for a 1980 movie, Up the Academy, directed by Robert Downey.

Feldstein, who will see the exhibit for the first time this week, takes an almost paternal pride in Alfred’s success.

“It was something I was extremely happy with that I have done.”

“Alfred, We Hardly Knew Thee!” continues through Feb. 7 in the Ford Gallery in Ford Hall at Eastern Michigan University in Ypsilanti. Ford Hall is north of Cross Street at the intersection of Normal Street. GalIery hours are 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Mon. and Thursday.; 10 a.m. to 7 p.m. Tuesday and Wednesday, and 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. Friday and Saturday. Closed Sunday. Information: 734-487-0465.

© 2007 The Blade